Indigenous Peoples' Conservation Area:

Nexus of Human Rights and Sustainability

Troy Abromaitis, Nlaka’pamux Citizen | Indigenous Survivors Day Founder

Dr. Daniel B. Sarvestani, Assistant Professor, ACSS Department, UCW

On August 9th, 2025, the International Day of Indigenous Peoples, members of the Indigenous Action Committee, including Troy Abromaitis and Daniel B. Sarvestani, gathered at Harrison Hot Springs to inaugurate the establishment of the Indigenous Peoples Conservation Area (IPCA) across the unceded territories of the Xa'xtsa (Douglas First Nation).

During this gathering, we were deeply honored to meet with Former Chief Darryl Peters. Alongside us was a dedicated marketing team and camera crew, including Cindy Melissa Vargas, as we worked to document and share the IPCA initiative taking shape on Xa’xtsa territory.

However, that day was not only about conservation. It was just as much about healing. Walking with us, Chief Darryl, carrying the grief of losing his wife only months before. Beside him, Troy carried the memory of losing his mother the year prior. Troy and Darryl, both leaders in their own right, walked these lands as mourners and defenders, finding in the earth beneath their feet and the waters around them a way to carry loss forward. This was just as much a ceremony of healing and learning as it was about conservation.

The IPCA represents far more than an environmental conservation plan. It embodies a philosophy and worldview that incorporates Indigenous Peoples’ ways of being and land-based learning into the conservation process (Artelle et al., 2019; Borrows, 2010). At its core, the IPCA works to preserve Indigenous sovereignty while promoting environmental sustainability and biodiversity. It is well known that some of the richest biospheres in the world, here in Canada and globally, are located on Indigenous lands (WWF, 2022; United Nations, 2021).

For too long, Eurocentric conservation systems-imposed models of national parks and protected areas that excluded Indigenous Peoples. These “fortress conservation” models alienated the original stewards of the land by portraying nature as separate from people and human activity (Brockington, Duffy, & Igoe, 2008). This reflects a Cartesian worldview that positions humans apart from nature (Latour, 1993). Historically, colonial authorities used conservation as a tool to dispossess Indigenous Peoples of their territories and disrupt ceremonies and cultural practices that connect them to the land (Simpson, 2014; Coulthard, 2014).

The IPCA, by contrast, builds upon Indigenous worldviews, which see humans as an integral and inseparable part of the land and natural world (Simpson, 2017; Wilson, 2008). This perspective does not place humans at the center of the universe or above nature but situates them within a web of life intricately woven through land and ecosystems (Kimmerer, 2013). The IPCA recognizes that Indigenous communities have always been the stewards of their territories, and that natural biospheres thrive when cared for through respectful, sustainable practices where humans coexist as part of the ecosystem (Artelle et al., 2019).

This approach aligns with international standards for Indigenous rights, such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (United Nations, 2007) and ILO Convention 169 (International Labour Organization, 1989), which unequivocally protect Indigenous Peoples and their right to live and thrive within their own territories. These frameworks acknowledge the vital role Indigenous communities play in protecting and sustaining some of the world’s most sensitive and biodiverse regions—from the Amazon Basin to cloud forests, boreal forests in British Columbia, and the vast savannas of Central Africa (United Nations, 2021; WWF, 2022).

Here on Turtle Island, this focus on sustainability resonates deeply with many First Nations communities. It reflects our shared responsibility to care for the land and all beings, and to ensure we pass it on in a good way to future generations (Borrows, 2010). For many First Nations in British Columbia, the land is a source of ceremony, medicine, and healing, not merely a place for recreation or “getting away” (Simpson, 2017; Wilson, 2008). Through conservation efforts that integrate Indigenous cultural revitalization and sovereignty, the IPCA fosters pride, resilience, and regeneration on traditional territories.

We were profoundly honored to walk these lands with Chief Deral, who shared stories connected to every landmark. Harrison Hot Springs holds a wealth of history and cultural meaning, from legendary Sasquatch sightings during full moons to tales of mermaids dwelling in the crystalline waterways. These stories reflect the deep interconnection between the land and the cultural knowledge it holds. Indeed, both Darryl and Troy found themselves held by these teachings. Their mourning became a form of land defense. Their steps across Xa’xtsa territory were both personal and a visible gesture of continuity, remembrance, renewal, and resistance. Conservation is a ceremony.

It was a privilege to have University Canada West (UCW) present in solidarity on this important day. Standing together on these traditional territories with Chief Deral symbolizes our shared commitment to honoring Indigenous sovereignty, advancing cultural resurgence, and implementing the IPCA in ways that uplift and empower the Xa’xtsa and First Nations across Turtle Island.

References

-

Artelle, K. A., Zurba, M., Bhattacharyya, J., Chan, D. E., Brown, K., Housty, J., & Moola, F. (2019). Supporting resurgent Indigenous-led governance: A nascent mechanism for just and effective conservation. Biological Conservation, 240, 108284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108284

-

Borrows, J. (2010). Drawing Out Law: A Spirit's Guide. University of Toronto Press.

-

Brockington, D., Duffy, R., & Igoe, J. (2008). Nature Unbound: Conservation, Capitalism and the Future of Protected Areas. Earthscan.

-

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. University of Minnesota Press.

-

International Labour Organization (ILO). (1989). C169 - Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169). Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org

-

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions.

-

Latour, B. (1993). We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press.

-

Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 1–25.

-

Simpson, L. B. (2017). As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance. University of Minnesota Press.

-

United Nations. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples

-

United Nations. (2021). The State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Rights to Land, Territories and Resources. United Nations Publications.

-

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing.

-

World Wildlife Fund (WWF). (2022). Living Planet Report 2022. Retrieved from https://www.worldwildlife.org

Honouring Truth and Reconciliation Through Erasure Poetry

Dr. Kaye Hare, Associate Professor, ACSS Department, UCW

Dr. Gitanjaly Chhabra, Assistant Professor, ACSS Department, UCW

Dr. Daniel B. Sarvestani, Assistant Professor, ACSS Department, UCW

On September 29, the University Canada West (UCW) community came together to honour National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, a day of remembrance, reflection, and responsibility.

Established by the Government of Canada in 2021 following the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), this national day calls upon all Canadians to remember the children who never returned home from residential schools and to stand in solidarity with Survivors, their families, and Indigenous Nations who continue to live with the intergenerational impacts of colonial policies and the residential school system (Government of Canada, 2021; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015).

Between the late 1800s and 1996, when the last residential school closed, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their families and forced into systems of assimilation designed to erase their languages, cultures, and identities. Many never returned home. Survivors have shared stories of trauma, neglect, and abuse that continue to reverberate through communities today. This was a cultural genocide (TRC, 2015; Fontaine, 2021).

At UCW, we are reminded that Truth and Reconciliation is not a single day of observance but an ongoing call to action, an invitation to learn, unlearn, and act in solidarity. It asks us to reimagine education as a space of healing, accountability, and transformation. This work is not achieved overnight, and the path forward is rarely smooth. Setbacks, disagreements, discomfort, and collective healing are all parts of this process. We must remain patient, inclusive, and willing to hold space for one another (Regan, 2010; Battiste, 2013).

During our event at UCW, our keynote faculty had the opportunity to share their perspectives and engage with decolonial frameworks and approaches to Truth and Reconciliation. Below are some of the insights shared by our facilitators on decoloniality and the ongoing work of truth and reconciliation.

Dr. Kathleen (Kaye) Hare:

“I understand decolonial work as an ongoing responsibility in my teaching, research, and service. By integrating Indigenous epistemologies through creative and reflexive approaches, I aim to make learning and teaching grounded in care and accountability.”

Dr. Gitanjaly Chhabra:

“As an educator and researcher, I see Truth and Reconciliation as a holistic journey of learning, unlearning, and reimagining relationships with Indigenous peoples, knowledge, and the land—in ways that honour collective healing for true reconciliation.”

These reflections remind us of the deep personal and professional responsibilities educators hold in the ongoing journey of reconciliation and truth-telling.

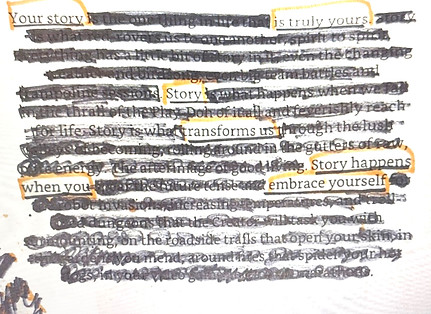

During the event, Dr. Hare and Dr. Chhabra invited participants to engage in erasure poetry, a creative practice that involves participants crossing out and finding words from a previously published piece to convey meaningful messages in new and imaginative ways. Poetry is often cited as an effective tool for reflection and resistance, inviting us to transform words into creative tools for transformation (Duarte, 2017; Simpson, 2017).

Below are some of the creative pieces shared by UCW faculty and community members during this meaningful workshop:

All in all conclusion, UCW’s initiative to honor National Day for Truth and Reconciliation by remembering and reflecting reaffirmed our shared commitment to learning, healing, and collective responsibility. The event underscored that reconciliation is a living, continuous process, rooted in empathy and action. Through reflective practices like erasure poetry and the insights of Dr. Hare and Dr. Chhabra, participants were invited to engage deeply with decolonial perspectives and reimagine education as a space for justice and care. UCW stands united in its dedication to amplify Indigenous voices and advancing meaningful pathways toward truth, justice, and reconciliation.

References

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Purich Publishing.

Duarte, C. (2017). Decolonizing through poetry: Indigenous resistance and renewal. Canadian Literature, 230, 15–37.

Fontaine, P. (2021, September 29). National Day for Truth and Reconciliation reminds us of the work still to be done. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/national-day-truth-reconciliation-opinion-1.6193030

Government of Canada. (2021). National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/campaigns/national-day-truth-reconciliation.html

Regan, P. (2010). Unsettling the settler within: Indian residential schools, truth telling, and reconciliation in Canada. UBC Press.

Simpson, L. B. (2017). As we have always done: Indigenous freedom through radical resistance. University of Minnesota Press.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Government of Canada.

The

Fried Bread

Dr. Wisanu (Aik) Krutngoen, Assistant Professor

ACSS Department, UCW

They were golden brown, they were crunchy from the outside but once you bite into it – it was soft and chewy with lightly sweet taste in its spongy texture. The were neatly arranged in the large silver tray, waiting for hungry mouths and hands to pick them up. They looked rather simple, but beautifully simple, just like you see them back home in your kitchen when your mum would prepare for on special Friday evenings because she knew you love those breads. Sometimes, when I was much younger, I would protest when mum made those bread too much too often - we all have those moments.

However, when I saw them in the first few seconds today, the simplicity of fried bread I see brought subtle feelings of comfort food, home, love and care, and pure intention. Feeling connected – I suddenly felt the surging gratitude filled up in my heart.

At the sacred and subtle naming ceremony I attended a few weeks ago at the University Canada West, there were fried breads made by the respected elders from the indigenous community, who attended along with our own UCW members to celebrate an important event to welcome an indigenous member Troy, into the community with true commitment to accept, to care, to nurture, and to be part of one another for life. The ceremony was done in a very simple yet rather intimate.

There were no fireworks, no loud music, no parade, no microphone announcement, no ribbon to cut, no champaign to pop open. The ceremony was done through the deep feelings of song sung melancholically to the attendees, along with beautiful personal stories entailed the deep wounds of survival being revealed. There were no hero stories, but tears and the tales of raw and repetitive struggles through the very dark paths of the indigenous community and in some of the attended elders, and how they survived. We sat in a circle quietly, looking into each other’s eyes – I saw reflections of me in theirs. There were also the gleam of lights and hopes, and the encouraging planning of how the community would come together, accept one another, and nurture each other. There were immense senses of reaching out, connecting, building, and healing. I witnessed one beautiful soul connected with the community, and one community to the others. As one cannot stay as an island amidst a vast ocean of turmoil streams, I sensed the heaviness of the indigenous community, and the cradle of love was strengthened and shared – as if I was part of them. And once the ceremony was done - I felt the surging gratitude filled up in my heart.

I reached out and grabbed one fried bread, and one bite into it, “how sweet and satisfy this was!” I thought to myself.